Questions for: Larissa de Souza

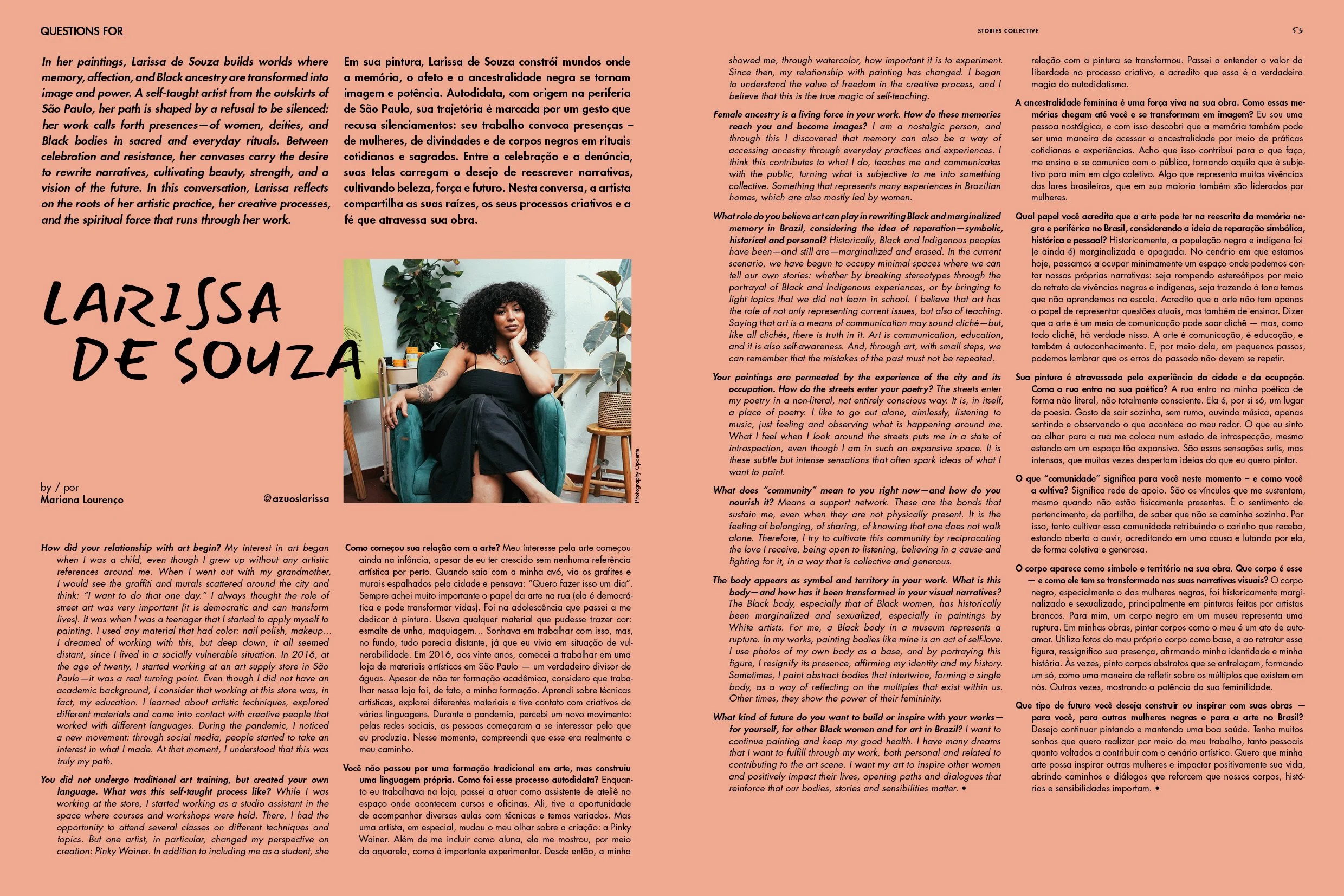

In her paintings, Larissa de Souza builds worlds where memory, affection, and Black ancestry are transformed into image and power. A self-taught artist from the outskirts of São Paulo, her path is shaped by a refusal to be silenced: her work calls forth presences — of women, deities, and Black bodies in sacred and everyday rituals. Between celebration and resistance, her canvases carry the desire to rewrite narratives, cultivating beauty, strength, and a vision of the future. In this conversation, Larissa reflects on the roots of her artistic practice, her creative processes, and the spiritual force that runs through her work.

BY/POR MARIANA LOURENÇO

How did your relationship with art begin?

My interest in art began when I was a child, even though I grew up without any artistic references around me. When I went out with my grandmother, I would see the graffiti and murals scattered around the city and think: “I want to do that one day.” I always thought the role of street art was very important (it is democratic and can transform lives). It was when I was a teenager that I started to apply myself to painting. I used any material that had color: nail polish, makeup… I dreamed of working with this, but deep down, it all seemed distant, since I lived in a socially vulnerable situation. In 2016, at the age of twenty, I started working at an art supply store in São Paulo—it was a real turning point. Even though I did not have an academic background, I consider that working at this store was, in fact, my education. I learned about artistic techniques, explored different materials and came into contact with creative people that worked with different languages. During the pandemic, I noticed a new movement: through social media, people started to take an interest in what I made. At that moment, I understood that this was truly my path.

You did not undergo traditional art training, but created your own language. What was this self-taught process like?

While I was working at the store, I started working as a studio assistant in the space where courses and workshops were held. There, I had the opportunity to attend several classes on different techniques and topics. But one artist, in particular, changed my perspective on creation: Pinky Wainer. In addition to including me as a student, she showed me, through watercolor, how important it is to experiment. Since then, my relationship with painting has changed. I began to understand the value of freedom in the creative process, and I believe that this is the true magic of self-teaching.

Female ancestry is a living force in your work. How do these memories reach you and become images?

I am a nostalgic person, and through this I discovered that memory can also be a way of accessing ancestry through everyday practices and experiences. I think this contributes to what I do, teaches me and communicates with the public, turning what is subjective to me into something collective. Something that represents many experiences in Brazilian homes, which are also mostly led by women.

What role do you believe art can play in rewriting black and marginalized memory in Brazil, considering the idea of reparation—symbolic, historical and personal?

Historically, black and indigenous peoples have been—and still are—marginalized and erased. Where we are today, we have begun to occupy minimal spaces where we can tell our own stories: whether by breaking stereotypes through the portrayal of black and indigenous experiences, or by bringing to light topics that we did not learn in school. I believe that art has the role of not only representing current issues, but also of teaching. Saying that art is a means of communication may sound cliché—but, like all clichés, there is truth in it. Art is communication, education, and it is also self-awareness. And, through art, with small steps, we can remember that the mistakes of the past must not be repeated.

Your paintings are permeated by the experience of the city and its occupation. How do the streets enter your poetry?

The streets enter my poetry in a non-literal, not entirely conscious way. It is, in itself, a place of poetry. I like to go out alone, aimlessly, listening to music, just feeling and observing what is happening around me. What I feel when I look around the streets puts me in a state of introspection, even though I am in such an expansive space. It is these subtle but intense sensations that often spark ideas of what I want to paint.

What does “community” mean to you right now—and how do you nourish it?

Means a support network. These are the bonds that sustain me, even when they are not physically present. It is the feeling of belonging, of sharing, of knowing that one does not walk alone. Therefore, I try to cultivate this community by reciprocating the love I receive, being open to listening, believing in a cause and fighting for it, in a way that is collective and generous.

The body appears as symbol and territory in your work. What is this body—and how has it been transformed in your visual narratives?

The black body, especially that of black women, has historically been marginalized and sexualized, especially in paintings by white artists. For me, a black body in a museum represents a rupture. In my works, painting bodies like mine is an act of self-love. I use photos of my own body as a base, and by portraying this figure, I resignify its presence, affirming my identity and my history. Sometimes, I paint abstract bodies that intertwine, forming a single body, as a way of reflecting on the multiples that exist within us. Other times, they show the power of their femininity.

What kind of future do you want to build or inspire with your works—for yourself, for other black women and for art in Brazil?

I want to continue painting and keep my good health. I have many dreams that I want to fulfill through my work, both personal and related to contributing to the art scene. I want my art to inspire other women and positively impact their lives, opening paths and dialogues that reinforce that our bodies, stories and sensibilities matter.

EXTRA

There is a strong presence of sacred imagery in your works. What is the role of faith and spirituality in your work?

I am a spiritual person, and that is why I like to portray everything I experience, feel, think and believe. The theme of “faith,” in particular, has always fascinated me. Where I came from, faith was often the only possible answer to what seemed impossible.

Your work combines everyday emotions with sociopolitical struggles. How do you balance the intimate and the collective in your painting?

Actually, I never stopped to think about how to balance the intimate and the collective in my paintings. Maybe everything starts as something deeply intimate (even when it is also collective). I portray the world based on how I have been impacted by it. It is my way of giving form to what I feel, and in this process, I discovered that what is mine can also belong to many.

Art is a celebration, but it also carries pain and criticism. How do you articulate these tensions between beauty, humor, affection and strength in your creations?

My paintings hold humor, but they also hold melancholy. I still do not know exactly how to articulate these emotions, perhaps because everything comes out so earnestly. Sometimes I feel like I am part of what I paint. I do not rationalize too much… It just happens. It is as if the painting penetrates me before I even understand what it wants to say.

Em sua pintura, Larissa de Souza constrói mundos onde a memória, o afeto e a ancestralidade negra se tornam imagem e potência. Autodidata, com origem na periferia de São Paulo, sua trajetória é marcada por um gesto que recusa silenciamentos: seu trabalho convoca presenças – de mulheres, de divindades, de corpos negros em rituais cotidianos e sagrados. Entre a celebração e a denúncia, suas telas carregam o desejo de reescrever narrativas, cultivando beleza, força e futuro. Nesta conversa, a artista compartilha as suas raízes, processos criativos e a fé que atravessa sua obra.

Como começou sua relação com a arte?

Meu interesse pela arte começou ainda na infância, apesar de eu ter crescido sem nenhuma referência artística por perto. Quando saía com a minha avó, via os grafites e murais espalhados pela cidade e pensava: “Quero fazer isso um dia”. Sempre achei muito importante o papel da arte na rua (ela é democrática e pode transformar vidas). Foi na adolescência que passei a me dedicar à pintura. Usava qualquer material que pudesse trazer cor: esmalte de unha, maquiagem… Sonhava em trabalhar com isso, mas, no fundo, tudo parecia distante, já que eu vivia em situação de vulnerabilidade. Em 2016, aos vinte anos, comecei a trabalhar em uma loja de materiais artísticos em São Paulo – um verdadeiro divisor de águas. Apesar de não ter formação acadêmica, considero que trabalhar nessa loja foi, de fato, a minha formação. Aprendi sobre técnicas artísticas, explorei diferentes materiais e tive contato com criativos de várias linguagens. Durante a pandemia, percebi um novo movimento: pelas redes sociais, as pessoas começaram a se interessar pelo que eu produzia. Nesse momento, compreendi que esse era realmente o meu caminho.

Você não passou por uma formação tradicional em arte, mas construiu uma linguagem própria. Como foi esse processo autodidata?

Enquanto eu trabalhava na loja, passei a atuar como assistente de ateliê no espaço onde acontecem cursos e oficinas. Ali, tive a oportunidade de acompanhar diversas aulas com técnicas e temas variados. Mas uma artista, em especial, mudou o meu olhar sobre a criação: a Pinky Wainer. Além de me incluir como aluna, ela me mostrou, por meio da aquarela, como é importante experimentar. Desde então, a minha relação com a pintura se transformou. Passei a entender o valor da liberdade no processo criativo, e acredito que essa é a verdadeira magia do autodidatismo.

A ancestralidade feminina é uma força viva na sua obra. Como essas memórias chegam até você e se transformam em imagem?

Eu sou uma pessoa nostálgica, e com isso descobri que a memória também pode ser uma maneira de acessar a ancestralidade por meio de práticas cotidianas e experiências. Acho que isso contribui para o que faço, me ensina e se comunica com o público, tornando aquilo que é subjetivo para mim em algo coletivo. Algo que representa muitas vivências dos lares brasileiros, que em sua maioria também são liderados por mulheres.

Qual papel você acredita que a arte pode ter na reescrita da memória negra e periférica no Brasil, considerando a ideia de reparação – simbólica, histórica e pessoal?

Historicamente, a população negra e indígena foi – e ainda é – marginalizada e apagada. No cenário em que estamos hoje, passamos a ocupar minimamente um espaço onde podemos contar nossas próprias narrativas: seja rompendo estereótipos por meio do retrato de vivências negras e indígenas, seja trazendo à tona temas que não aprendemos na escola. Acredito que a arte não tem apenas o papel de representar questões atuais, mas também de ensinar. Dizer que a arte é um meio de comunicação pode soar clichê – mas, como todo clichê, há verdade nisso. A arte é comunicação, é educação, e também é autoconhecimento. E, por meio dela, em pequenos passos, podemos lembrar que os erros do passado não devem se repetir.

Sua pintura é atravessada pela experiência da cidade e da ocupação. Como a rua entra na sua poética?

A rua entra na minha poética de forma não literal, não totalmente consciente. Ela é, por si só, um lugar de poesia. Gosto de sair sozinha, sem rumo, ouvindo música, apenas sentindo e observando o que acontece ao meu redor. O que eu sinto ao olhar para a rua me coloca num estado de introspecção, mesmo estando em um espaço tão expansivo. São essas sensações sutis, mas intensas, que muitas vezes despertam ideias do que eu quero pintar.

O que “comunidade” significa para você neste momento – e como você a cultiva?

Significa rede de apoio. São os vínculos que me sustentam, mesmo quando não estão fisicamente presentes. É o sentimento de pertencimento, de partilha, de saber que não se caminha sozinha. Por isso, tento cultivar essa comunidade retribuindo o carinho que recebo, estando aberta a ouvir, acreditando em uma causa e lutando por ela, de forma coletiva e generosa.

O corpo aparece como símbolo e território na sua obra. Que corpo é esse – e como ele tem se transformado nas suas narrativas visuais?

O corpo negro, especialmente o das mulheres negras, foi historicamente marginalizado e sexualizado, principalmente em pinturas feitas por artistas brancos. Para mim, um corpo negro em um museu representa uma ruptura. Em minhas obras, pintar corpos como o meu é um ato de autoamor. Utilizo fotos do meu próprio corpo como base, e ao retratar essa figura, ressignifico sua presença, afirmando minha identidade e minha história. Às vezes, pinto corpos abstratos que se entrelaçam, formando um só, como uma maneira de refletir sobre os múltiplos que existem em nós. Outras vezes, mostrando a potência da sua feminilidade.

Que tipo de futuro você deseja construir ou inspirar com suas obras – para você, para outras mulheres negras e para a arte no Brasil?

Desejo continuar pintando e mantendo uma boa saúde. Tenho muitos sonhos que quero realizar por meio do meu trabalho, tanto pessoais quanto voltados a contribuir com o cenário artístico. Quero que minha arte possa inspirar outras mulheres e impactar positivamente suas vidas, abrindo caminhos e diálogos que reforcem que nossos corpos, histórias e sensibilidades importam.

EXTRAS

Há em suas obras uma forte presença do sagrado. Qual é o papel da fé e da espiritualidade no seu trabalho?

Sou uma pessoa espiritualizada, e por isso gosto de retratar tudo aquilo que vivencio, sinto, penso e acredito. O tema da “fé”, de forma particular, sempre me encantou. No lugar de onde vim, a fé, muitas vezes, era a única resposta possível diante daquilo que parecia impossível.

Sua obra combina afetos do cotidiano com tensões sociopolíticas. Como você equilibra o íntimo e o coletivo na sua pintura?

Na verdade, eu nunca tinha parado para pensar em como equilibrar o íntimo e o coletivo nas minhas pinturas. Talvez tudo comece como algo profundamente íntimo (mesmo quando também é coletivo). Eu retrato o mundo a partir de como fui impactada por ele. É a minha maneira de dar forma àquilo que sinto, e nesse processo, descobri que o que é meu também pode ser de muitos.

Arte é celebração, mas também carrega dor e denúncia. Como você articula essas tensões entre beleza, humor, afeto e força nas suas criações?

Minhas pinturas têm humor, mas também têm melancolia. Ainda não sei exatamente como articular essas emoções, talvez porque tudo surja de forma muito sincera. Às vezes, sinto que sou parte daquilo que pinto. Não racionalizo demais… Simplesmente acontece. É como se a pintura me atravessasse antes mesmo de eu entender o que ela quer dizer