The Nanasístico Pact of Blackness: Inclusion and collectivity in the visual arts

BY/POR RENATA FELINTO

I have many doubts about what we generally call “inclusion”, and more specifically, in the cultural industry and the visual arts. First, when we use the term inclusion, we implicitly accept the existence of exclusion. However, when people who make up excluded, marginalized, or invisible groups point out their condition, they are often labeled as “playing the victim,” as if, in fact, there were no structural exclusion taking place. The term “victimhood” is a silencing response, a strategy that imposes humiliation, resignation, and guilt on those targeted, operating an inversion of meanings aimed at ensuring the perpetuation of dominant structures. This mechanism not only discredits complaints but also reinforces oppression by distorting historical responsibility, maintaining unchanged the conditions that produce and sustain inequalities of values and meanings. This becomes even more complex and perverse when we look at the visual arts industry, not only in Brazil but in the Western world as a whole, which, unfortunately, shapes our ways of thinking (in Portuguese), of relating to one another, of loving, and of living.

Despite this dishonest maneuver, systematically used in Brazil, we non-white people have, for generations, dealt every day with the remnants of the colonial project that ended up colonizing relationships in all areas of human coexistence. For Black and Indigenous cisgender women, the exploitation of their body as labor force persists, as an object of sexual entertainment for our tormentors, and as a workforce that, due to precarious access to basic rights and resources, aims to feed back into the gears of capitalism. In this Westernized context, our world-systems have been underestimated, omitted, distorted, and their erasure has even been practiced by formal education institutions. As if our existence and contributions to the history of humanity in the West—and, consequently, to culture and the visual arts—were of lesser relevance, when, in fact, they are revisited and appropriated as reference sources for white-centric cultural and artistic “innovations.”

Thus, since everyone knows who, how, why and since when people are excluded, the concept of “inclusion” is often made empty, as it does not consider the depth of the historical, cultural and symbolic violence suffered by non-white populations.

When discussing inclusion, we must reflect on what is actually being “included” and what the true foundation of this inclusion is. Is it true inclusion, capable of altering power structures, or merely a superficial one that reinforces established norms, disguised as representation and visibility? This question demands deeper reflection on inclusive measures in the visual arts systems and their social and political implications, challenging notions of access and participation that continue to be shaped by the same forces that sustain exclusion.

Furthermore, when reflecting on inclusion, we must consider the profound implications of whiteness as a system of power, privilege, and control, which insists on tokenizing and treating our ontologies and cosmologies as exotic, immature, and unreal. This systematic reduction disregards the longevity and complexity of our collective identities, which, especially in the case of Afro-diasporic people, have been fragmented and transformed over centuries of separation from our continent of origin, but still shape central aspects of our lives, particularly internally, within our communities and institutions.

The same is true of Indigenous peoples, who, whether living in villages or not, preserve practices of coexistence, spirituality, and love that diverge from those we have learned are “valid” in the white Western world. Furthermore, reflecting on these aspects, understanding that the notion of collectivity coexists with those of subjectivity, individuality, and freedom, seems incredibly challenging for those who confine us to agendas rather than rights.

The question then arises: Can these identities be included without continuing to be seen through the prism of exoticization, as figures of otherness, rather than recognized as an integral part of humanity? Could our heritages, lineages, spiritualities, realities, inventiveness, and visuals be considered as legitimate as those crystallized by epistemologies that linearly document a historical fiction considered coherent, but which, paradoxically, excludes significant parts of humanity in order to be consolidated?

Identities were (and perhaps still are) an honest reflection on our authenticity and plurality, which makes us unique, yet diverse, as human beings. But if this is true, why have we not yet included whiteness—both the system and the identity—as just one of the possible configurations of the world’s population? Why do we still interpret and situate ourselves based on it, as if it were the only legitimate and recognized identity on a global scale?

This leads us to rethink the construction of identities in the context of relationships established socially, culturally, and in the visual arts, acknowledging that true inclusion will occur only when these issues are addressed in a way that challenges not only references, visibility, and representation, but also the very power structures that sustain the dominant historical narrative. Inclusion, therefore, must mean more than simply absorbing marginalized identities into a system that continues to treat them as “others:” it must be a radical reconfiguration of the epistemologies and practices that determined who would be marginalized.

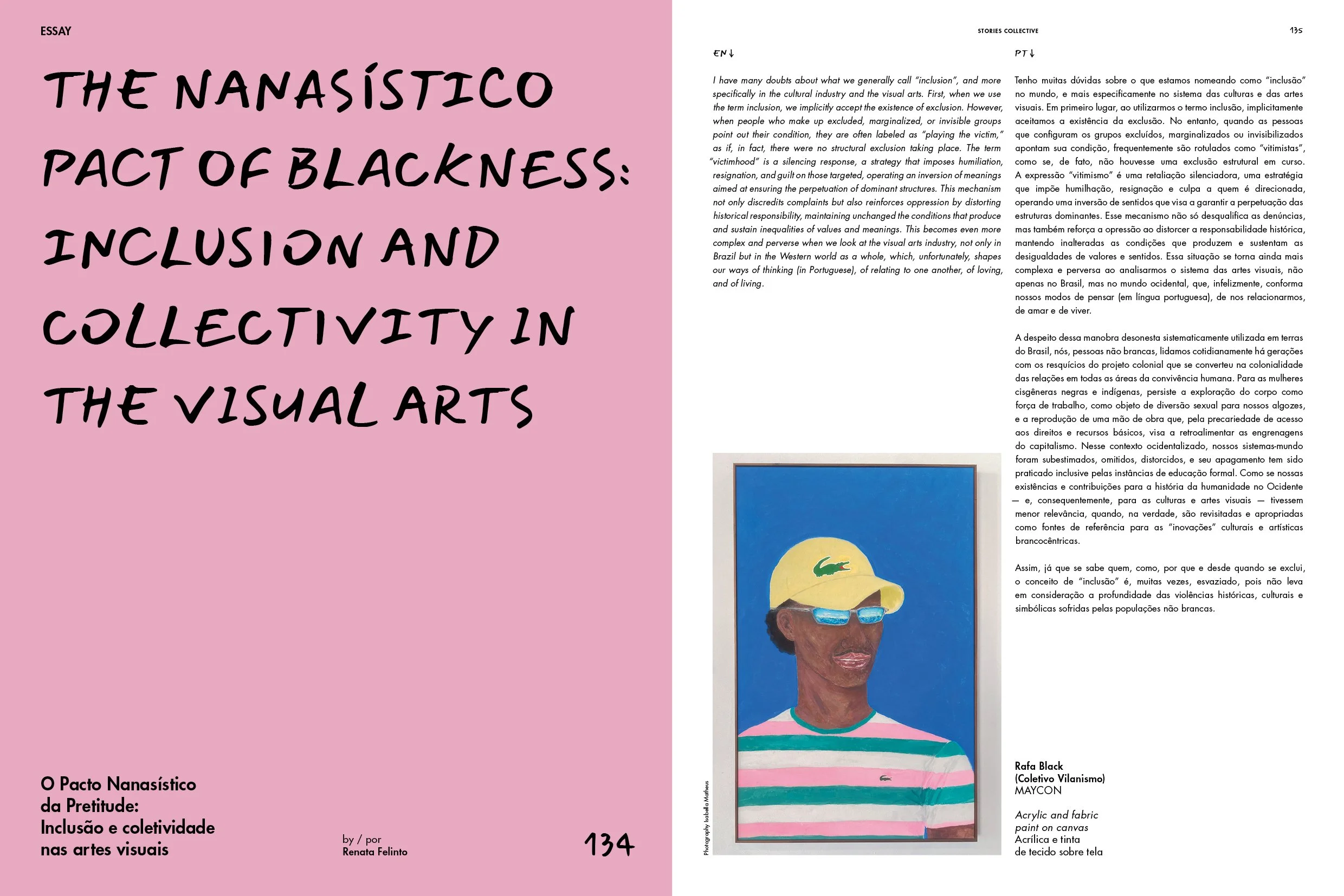

In this context, collectives, gatherings, and quilombos of non-white people in the visual arts field have been reactions to naturalized exclusionary actions. Among the most radical initiatives we have witnessed recently, we can highlight Coletivismo Vilanismo, formed by Black male visual artists from the outskirts of São Paulo, who will be at the 36th São Paulo Bienal this year. Vilanismo emerged as a form of resistance in an urban context of invisibility and marginalization. Founded in 2021, Vilanismo is composed of twelve Black men and aims to create spaces of resistance and affirmation in the artistic circuit. The collective values ancestral Afro-Indigenous knowledge, collaborative practices, and autonomy, rejecting historical stereotypes and celebrating Black culture.

Additionally, we mention Levante Nacional TROVOA, a hybrid gathering—online and in-person—founded in 2017 in Rio de Janeiro. Formed by visual artists and curators of color—cis and trans women from various regions of Brazil—TROVOA aims to promote the inclusion of Black and non-white artists in the art system, highlighting non-hegemonic productions and the plurality of artistic discourses and languages.

In the Cariri region of the state of Ceará, Bixórdia is an independent research and creative lab founded in 2019, bringing together artists from the performing and visual arts, with a focus on promoting sexual and gender diversity. Bixórdia works to combat LGBTIphobia, raising awareness of LGBTQIAP+ issues through art education, and developing exhibitions, discussion groups, and initiatives focusing on local culture.

The specificities and common commitments that converge in these quilombos—Vilanismo, Levante Nacional TROVOA and Bixórdia—are shaped by the experiences of excluded humanities who recognize their weakness and potential, relating and organizing themselves based on this awareness, with the inclusion of affection in their work, creation, management and exhibits.

These collectives are spaces of resistance, whether physical or not, in which experiences marked by exclusion, the sharing of diverse experiences, and collaborative practices become central. Affection, often neglected in formal and hegemonic spaces, finds in these initiatives a point of convergence that redefines artistic development and forges strategies of protection and community for institutional confrontation.

The supposed premises of neutrality, impartiality, assertiveness, and competence often attributed to arts and culture institutions in the corporate world—which claim to be universal and for everyone—are, in fact, simulations that evolve as the stakeholders and their gender, race, class, and geographic characteristics change. These institutions, predominantly run by white people, are not immune to the processes of exclusion they themselves sustain and reproduce, even under the guise of false equality. The apparent impartiality of these spaces camouflages a profound bias that only becomes visible when non-white bodies or marginalized identities turn into protagonists in the arts.

And as we become protagonists, we need to establish another agreement: the Nanasístico Pact of Blackness. I have been developing this concept, which proposes the reconfiguration of power dynamics, where relationships of affection and collectivity are more than just instruments for superficial inclusion. They become practices of resistance, care, protection, security, and affirmation of the existence and power of humanities that have historically been violated. The Nanasístico Pact of Blackness, therefore, invites the reinvention of relationships between subjects and spaces, using the memory of Afro-diasporic cultural and artistic practices as a foundation for building new forms of organization and creation. It does not propose simple integration into a failed system, but rather the creation of a new system that not only recognizes but celebrates the pluralities of identity, experience, and affection that constitute our realities.

Within the Nanasístico Pact of Blackness, the practice extends to collectives of visual artists, managers, critics—that is, to all professionals within the visual arts system. It aims to reconfigure artistic and curatorial practices based on Black, Indigenous, and dissident epistemologies, recognizing and valuing knowledge that has been historically erased. The Pact proposes that the visual arts system and its professionals not replicate colonized structures that benefit only a select group, but rather operate as agents of transformation, recognizing their privileged place and promoting aesthetic justice and reparation as their guiding ethics. Building a collective and democratic space in the visual arts, one that transcends hierarchies and Eurocentric norms, is essential for the revitalization of the visual arts field.

In this context, the Nanasístico Pact of Blackness proposes an ethical commitment among art professionals, where listening to and recognizing diverse forms of creation, production, and critique are actively practiced. Rather than perpetuating a closed-off system that favors whiteness as its sole paradigm, the Pact aims to decentralize symbolic, financial, and historical power, encouraging a modus operandi that, rather than isolating or remaining within the framework of colonial ownership and isolation, opens space for sharing and collaboration. This pact seeks to transform relationships within the artistic system, where the protagonism of Black, Indigenous, and dissident communities is celebrated, not feared, reimagining art as a field of resistance and justice, where diverse narratives and aesthetics can coexist and mutually strengthen each other.

Genuine inclusion in the visual arts requires the boldness of quilombos and collectives, not in isolated individual identities, but in artistic villages that are configured as spaces of resistance, solidarity, sharing, and affirmation. These collectives, as forms of artistic community, go beyond the logic of competition and individualism, creating networks of solidarity that celebrate the plurality and diversity of knowledge. By organizing into villages, artists and visual arts professionals form territories of belonging and transformation where creation is not a solitary act, but a collective process that seeks historical reparation and aesthetic justice. In these spaces, art ceases to be merely a reflection of dominant narratives, becoming a living force for reconfiguration and the construction of a more inclusive and plural future. Let us make this pact!

O Pacto Nanasístico da Pretitude: Inclusão e coletividade nas artes visuais

Tenho muitas dúvidas sobre o que estamos nomeando como “inclusão” no mundo, e mais especificamente no sistema das culturas e das artes visuais. Em primeiro lugar, ao utilizarmos o termo inclusão, implicitamente aceitamos a existência da exclusão. No entanto, quando as pessoas que configuram os grupos excluídos, marginalizados ou invisibilizados apontam sua condição, frequentemente são rotulados como “vitimistas”, como se, de fato, não houvesse uma exclusão estrutural em curso. A expressão “vitimismo” é uma retaliação silenciadora, uma estratégia que impõe humilhação, resignação e culpa a quem é direcionada, operando uma inversão de sentidos que visa a garantir a perpetuação das estruturas dominantes. Este mecanismo não só desqualifica as denúncias, mas também reforça a opressão ao distorcer a responsabilidade histórica, mantendo inalteradas as condições que produzem e sustentam as desigualdades de valores e sentidos. Essa situação se torna ainda mais complexa e perversa ao analisarmos o sistema das artes visuais, não apenas no Brasil, mas no mundo ocidental, que, infelizmente, conforma nossos modos de pensar (em língua portuguesa), de nos relacionarmos, de amar e de viver.

A despeito desta manobra desonesta sistematicamente utilizada em terras do Brasil, nós, pessoas não brancas, lidamos cotidianamente há gerações com os resquícios do projeto colonial que se converteu na colonialidade das relações em todas as áreas da convivência humana. Para as mulheres cisgêneras negras e indígenas, persiste a exploração do corpo como força de trabalho, como objeto de diversão sexual para nossos algozes, e a reprodução de uma mão de obra que, pela precariedade de acesso aos direitos e recursos básicos, visa a retroalimentar as engrenagens do capitalismo. Nesse contexto ocidentalizado, nossos sistemas-mundo foram subestimados, omitidos, distorcidos, e seu apagamento tem sido praticado inclusive pelas instâncias de educação formal. Como se nossas existências e contribuições para a história da humanidade no ocidente — e, consequentemente, para as culturas e artes visuais — tivessem menor relevância, quando, na verdade, são revisitadas e apropriadas como fontes de referência para as “inovações” culturais e artísticas brancocêntricas.

Assim, já que se sabe quem, como, por que e desde quando se exclui, o conceito de “inclusão” é, muitas vezes, esvaziado, pois não leva em consideração a profundidade das violências históricas, culturais e simbólicas sofridas pelas populações não brancas.

Ao falar de inclusão, devemos refletir sobre o que realmente está sendo “incluso” e qual é a base real dessa inclusão. Seria ela uma inclusão verdadeira, capaz de alterar as estruturas de poder, ou apenas uma inclusão superficial que reforça as normas estabelecidas, disfarçada de representatividade e visibilidade? Este questionamento exige uma reflexão mais profunda sobre as medidas inclusivas no sistema das artes visuais e suas implicações sociais e políticas, desafiando as noções de acesso e participação que continuam a ser moldadas pelas mesmas forças que sustentam a exclusão.

Além disso, ao refletirmos sobre inclusão, devemos considerar a profundidade das implicações da branquitude enquanto sistema de poder, privilégios e controle, que insiste em folclorizar e tratar nossas ontologias e cosmologias como pautas exóticas, imaturas, irreais. Essa redução sistemática desconsidera a longevidade e a complexidade das nossas identidades coletivas, que, embora, especialmente no caso das pessoas afro-diaspóricas, tenham sido fragmentadas e transformadas ao longo dos séculos de distanciamento do continente de origem, ainda moldam aspectos centrais de nossas vidas, particularmente internamente, em nossas comunidades e instituições.

O mesmo ocorre com os povos indígenas, que, aldeados ou não, preservam práticas de convivência, espiritualidade e amorosidade que divergem daquelas que aprendemos serem as “validadas” pelo mundo branco ocidental. Além disso, refletir sobre esses aspectos, compreendendo que a noção de coletividade coexiste com as de subjetividade, individualidade e liberdade, parece arduamente desafiador para aqueles que nos enclausuram em pautas, em vez de em direitos.

A pergunta que se coloca, então: é possível incluir essas identidades sem que continuemos sendo vistas e vistos sob o prisma da exotização, como figuras de outridade, em vez de nos reconhecerem como parte integral da humanidade? Nossas heranças, linhagens, espiritualidades, realidades, inventividades e visualidades poderiam ser consideradas tão legítimas quanto aquelas cristalizadas pelas epistemologias que documentam linearmente uma ficção histórica tida como coerente, mas que, paradoxalmente, exclui partes significativas da humanidade para consolidá-la?

As identidades foram (e talvez ainda sejam) uma reflexão honesta sobre nossa autenticidade e pluralidade, que nos torna singulares, ainda que diversificados enquanto seres humanos. Mas se isso é verdade, por quais motivos ainda não incluímos a branquitude — tanto o sistema quanto a identidade — como uma das configurações possíveis de população no mundo? Por que ainda nos lemos e nos situamos a partir dela, como se fosse a única identidade legítima e reconhecida no âmbito global?

Essa reflexão nos leva a repensar a construção das identidades no contexto das relações sociais, culturais e das artes visuais, reconhecendo que a verdadeira inclusão só ocorrerá quando essas questões forem abordadas de forma a questionar não apenas a representação, a visibilidade e a representatividade, mas também as próprias estruturas de poder que sustentam a narrativa histórica dominante. A inclusão, portanto, precisa ser mais do que uma simples absorção de identidades marginalizadas em um sistema que continua a tratá-las como “outras”: ela deve ser uma reconfiguração radical das epistemologias e práticas que estabeleceram essas margens.

Nesse contexto, as coletividades, ajuntamentos e aquilombamentos de pessoas não brancas no campo das artes visuais têm sido reações às ações de exclusão já naturalizadas. Entre as malungagens mais radicais que temos acompanhado recentemente, podemos destacar o Coletivismo Vilanismo, formado por artistas visuais homens negros das periferias de São Paulo, que este ano estarão na 16ª Bienal Internacional de São Paulo. O Vilanismo surgiu como forma de resistência em um contexto urbano de invisibilidade e marginalização. Fundado em 2021, o Vilanismo é composto por doze homens negros e tem como objetivo criar espaços de resistência e afirmação no circuito artístico. O coletivo valoriza os conhecimentos ancestrais afro-indígenas, práticas colaborativas e autonomia, rejeitando estereótipos históricos e celebrando a cultura negra.

Além disso, mencionamos o Levante Nacional TROVOA, um ajuntamento híbrido — virtual e presencial — fundado em 2017 no Rio de Janeiro. Formado por artistas visuais e curadoras racializadas — mulheres cis e trans de diversas regiões do Brasil —, o TROVOA tem o objetivo de promover a inclusão de artistas negras e não-brancas no sistema de arte, evidenciando produções não hegemônicas e a pluralidade de discursos e linguagens artísticas.

Na região do Cariri, Ceará, o Bixórdia é um laboratório de estudos e criação independente criado em 2019, reunindo artistas das artes cênicas e visuais, com foco na promoção da diversidade sexual e de gênero. O Bixórdia atua no combate à LGBTIfobia, visibilizando questões LGBTQIAP+ por meio da arte-educação, desenvolvendo exposições, rodas de conversa e ações com ênfase na cultura local.

As especificidades e comprometimentos comuns que confluem nos aquilombamentos mencionados — Vilanismo, Levante Nacional TROVOA e o Bixórdia — são conformados pelas experiências de humanidades excluídas que se reconhecem nas suas fragilidades e potencialidades, relacionando-se e se organizando a partir dessa consciência, com a inclusão do afeto nas relações de trabalho, criação, gestão e exibição.

Tais coletivos constituem espaços de resistência, físicos ou não, nos quais as vivências pautadas pela exclusão, a escuta das experiências diversas e a prática colaborativa se tornam centrais. O afeto, muitas vezes negligenciado em espaços formais e hegemônicos, encontra nessas iniciativas um ponto de convergência que ressignifica o devir artístico e forja estratégias de proteção e de comunhão no enfrentamento institucional.

As supostas premissas de neutralidade, imparcialidade, assertividade e competência, frequentemente atribuídas às instituições de arte e cultura no mundo corporativo — que se dizem universais e para todos —, são, na verdade, simulações que se moldam conforme mudam os interlocutores e suas características de gênero, raça, classe e geografia. Essas instituições, predominantemente geridas por pessoas brancas, não estão imunes aos processos de exclusão que elas mesmas sustentam e reproduzem, ainda que sob o disfarce da falsa equidade. A aparente imparcialidade desses espaços camufla uma profunda parcialidade que só é visível quando os corpos não brancos ou as identidades marginalizadas se tornam protagonistas no campo das artes.

E ao tornarmo-nos protagonistas, precisamos estabelecer um outro acordo: o Pacto Nanasístico da Pretitude. Venho construindo esse conceito que propõe a reconfiguração das dinâmicas de poder, onde as relações de afeto e coletividade são mais do que apenas instrumentos de inclusão superficial. Elas se tornam práticas de resistência, de cuidado, de proteção, de segurança e de afirmação da existência e da potência das humanidades que, historicamente, foram violentadas. O Pacto Nanasístico da Pretitude convida, portanto, à reinvenção das relações entre sujeitos e espaços, utilizando a memória das práticas culturais e artísticas afro-diaspóricas como alicerce para construir novas formas de organização e criação. Ele não propõe a simples integração em um sistema já falido, mas sim a criação de um novo sistema, que não só reconhece, mas celebra as pluralidades de identidade, experiência e afetividade que constituem as nossas realidades.

No Pacto Nanasístico da Pretitude, a prática se estende às coletividades de artistas visuais, gestores e gestoras, críticos e críticas, ou seja, a todos os profissionais que compõem o sistema das artes visuais. Trata-se de reconfigurar as práticas artísticas e curatoriais a partir de epistemologias negras, indígenas e dissidentes, reconhecendo e valorizando saberes que foram historicamente subtraídos. O pacto propõe que o sistema das artes visuais e seus profissionais não repliquem as estruturas coloniais que beneficiam apenas um seleto grupo, mas que operem como agentes de transformação, reconhecendo seu lugar de privilégio e promovendo a justiça estética e a reparação como éticas orientadoras. A construção de um espaço coletivo e democrático nas artes visuais, que transcenda as hierarquias e as normativas eurocêntricas, é essencial para a revitalização do campo das artes visuais.

Nesse contexto, o Pacto Nanasístico da Pretitude propõe um compromisso ético entre os profissionais da arte, onde a escuta e o reconhecimento das diversas formas de criação, produção e crítica sejam praticados ativamente. Em vez de perpetuar um sistema fechado que favorece a branquitude como único paradigma, o pacto visa à descentralização do poder simbólico, financeiro, histórico, incentivando um modus operandi que, em vez de se isolar ou se manter no âmbito da posse e isolamento coloniais, abra espaço para a partilha e a colaboração. Esse pacto busca transformar as relações no sistema artístico, onde o protagonismo das coletividades negras, indígenas e dissidentes seja celebrado, e não temido, reimaginando a arte como um campo de resistência e justiça, onde as diversas narrativas e estéticas possam coexistir e se fortalecer mutuamente.

Uma legítima inclusão nas artes visuais exige a ousadia de se aquilombar e se coletivizar, não em identidades individuais isoladas, mas em aldeamentos artísticos que se configuram como espaços de resistência, solidariedade, compartilhamento e afirmação. Esses coletivos, como formas de comunidade artística, vão além da lógica da competição e do individualismo, criando redes de solidariedade que celebram a pluralidade e a diversidade de saberes. Ao se organizar em aldeamentos, os artistas e profissionais das artes visuais formam territórios de pertencimento e transformação em que a criação não é um ato solitário, mas um processo coletivo que busca a reparação histórica e a justiça estética. Nesses espaços, a arte deixa de ser apenas um reflexo de narrativas dominantes, tornando-se uma força viva de reconfiguração e de construção de um futuro mais inclusivo e plural. Façamos esse pacto!